United We’re Blinded by the Wolf of Consumerism

As I walk down the streets of downtown San Diego on a Saturday night, I observe flocks of people with shopping bags and glazed expressions, intoxicated from the rush of just having spent a good portion of their pay check at the mall.

Walking past the various clubs, I feel the vibrations of the bass and I can see herds of party-goers grazing on their cigarettes and booze. Inside the doors, I see men puffing up their chests and barking across the dance floor at nearly half-naked females, hoping their mating call will attract a suitable member of the opposite sex for fornication later on that night. Once I pass this scene, I am immediately bombarded with the stench of seared flesh. I turn and see the predator sitting down to consume its prey; he then boxes up the leftovers to bring home to his nest. I turn the corner and am confronted with looming billboards and flashing lights ominously trying to coax my will into purchasing this liquor, that new meal at McDonalds, or whatever unnecessary necessity is out on the market today.

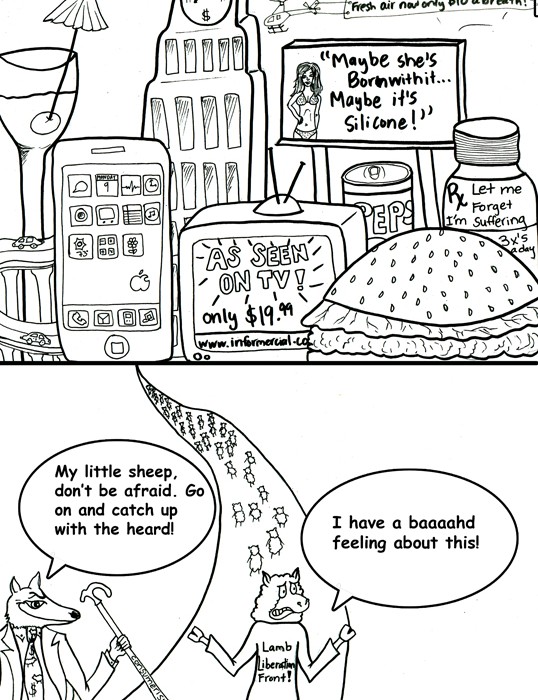

SHEEP AMIDST WOLVES

I cannot help but feel overwhelmed by sense-overload. Am I a mere sheep expected to blindly follow down a path seemingly laden with promises of lush greenery yet precariously set amongst many wolves? Can grazing on the pastures of unrestricted sense gratification bring me solace or real fulfillment?

It seems that few question the efficacy of a society who works very hard in order to indulge in primal, animalistic urges such as mating and eating flesh, and whose main purpose is making exorbitant amounts of money in order to satisfy one’s every whim via shopping sprees, intoxication, and mind-numbing television.

CONSUMERISM – SYMPTOM OF A MATERIALLY MOTIVATED SOCIETY

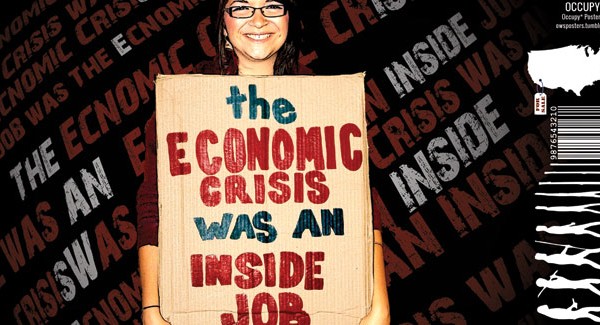

It is quite clear that the economic order of consumerism is an influential force in America. With the advent of the industrial and technological revolutions, products can be produced in larger quantities and at faster rates. Subsequently, corporations must now artificially impose a desire for their product, often times at the expense of the consumer’s well-being, in order to be successful.

Most of the population is hypnotized by the concept that material acquisition can make one happy. And with competition as the driving force, consumerism herds many down a path of ultimate dissatisfaction and subsequent disconnection, as we perform work for the sake of personal sense enjoyment.

Americans more and more are subscribing to a “culture of affluence,” a term in psychology which describes a culture that values ‘stuff’ over people, competition over cooperation, and the individual over the group (Levine, 2007). In other words, with so much value placed upon our external attachments and with an ever pressing need to make it to the top in society; we end up exploiting persons and things around us for our own personal benefit.

We exploit animals for the satisfying taste of their flesh, we exploit our lovers and once they no longer satisfy our mind and senses we divorce, and wars are fought over the exploitation of the natural resources. With our personal enjoyment at jeopardy, why let things like solidarity, service, or reciprocity get in the way, right? Such unscrupulous behavior is clearly a source of suffering, yet it’s the trend in most affluent countries—the consequences of which can be seen in young adolescents in our country today.

AFFLUENCE-NOT AN INDICATION OF HAPPINESS

Most research regarding adolescent mental health finds that affluent teens and preteens, in both public and private schools, have the highest rates of some of the most substantial emotional problems of any group of kids in this country (Levine, 2007). From depression, anxiety disorders and substance abuse to psychosomatic disorders, the youth today are becoming more affected from the results of a consumerist society.

Yet, how can we blame them? Bodily-pleasure idolization is publicly displayed in every major source of influence such as television, magazines, mainstream radio and billboards. “Buy this car, eat this cheeseburger, look like this woman so you can be attractive for men, et cetera” and you will be happy and fulfilled. In fact, our culture of affluence suggests that one’s value can be based upon one’s ability to attain such external achievements and temporary material pleasure.

Researchers at Princeton University have found that there is no correlation between material affluence and genuine happiness (Quinones, 2006), calling the link an “illusion.” And the quest to live up to such an illusion leads to the misallocation of our precious time, where we accept dismal and lengthy commutes, which are stressful and aggravating, and we sacrifice time spent socializing with friends and loved ones due to long work hours (Quinones, 2006). Why do we do this to ourselves just to afford “nice things”? If we accept the premise that the consumption of commodities brings happiness, we will inevitably be distracted away from the true sources of our well-being.

QUEST FOR INTERNAL SATISFACTION – SYMPTOM OF INTELLIGENT LIFE

Why work so diligently all day only to enjoy the most basic material pleasures and comforts at night?

Although we all must perform some work in order to survive, we should really question the purpose behind it all. Am I working for temporary sense gratification, or am I working towards a higher goal? And furthermore, are my endeavors bringing about suffering or genuine fulfillment?

Even animals perform some labor to keep themselves alive and maintained, and they too enjoy basic material pleasures such as eating, sleeping, and mating. But a human’s ability to enjoy these activities in a more comfortable, sophisticated way does not equate to more pleasure or happiness, because these things in themselves are not the goal of life! Are we no better off than a hog or a dog; working solely for the purpose of gratifying the senses without questioning higher truth?

The truth is—those things that make us truly happy are things such as meaningful, compassionate friendship, love, knowledge, and selfless service to others. Making money makes us happy only in so far as it provides for us the basic necessities so that we may cultivate such things. Working solely to satisfy our outer whims, which consumerism puts forth as the means to an end, leaves us with a flickering sense of happiness, and ultimately we’re left frustrated due to lack of internal fulfillment.

So, unless we come to the point of sincerely questioning whether or not there is a higher purpose for which to work, instead of just our base desires to enjoy material pleasure, we are no better off than an animal.