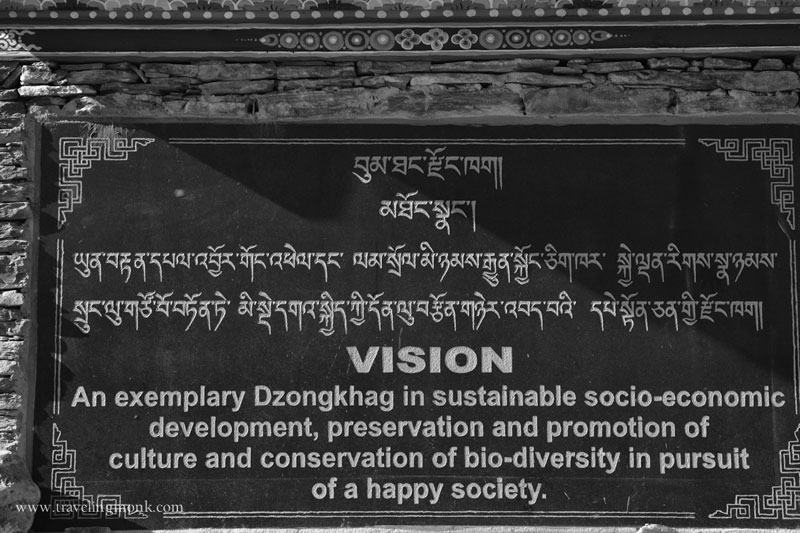

Bhutan is a small country situated at the eastern end of the Himalayas. Its population is slightly over 700,000. On the north it borders China and on all other sides it borders India.

Wholly Organic

Dr. Pema Gyamtsho, the country’s first democratically elected minister of Agriculture and Forests, announced earlier this year Bhutan’s plans to turn its agriculture completely organic. This plan includes a ban on sales of pesticides, herbicides, and artificial fertilizers.

This should not be too difficult of a task, for Bhutan is an overwhelmingly agrarian nation that was closed to foreign influences until a mere 30 years ago, when they opened their borders. Thus for a long time evading the contamination of what most modern people would consider progress, Bhutan managed to remain a pollution-free country where the cultivation of land is still largely done in traditional (read “organic”) ways.

By modern standards, Bhutan is rather a poor country. However, it is rich in natural goods: food, vegetation, and water, for example. Bhutan’s rivers help the country generate 2,000 megawatts of electrical energy, much of which is exported to India. Dr. Gyamtsho says that Bhutan has the potential to generate 10,000 megawatts of electrical energy.

In response to the concern that by going completely organic Bhutan’s food production may reduce and thus place its citizens in general and farmers in particular in a difficult situation, Bhutan’s government says that is a misconception. In the modern world people generally think that the use of pesticides and herbicides is necessary, lest the size of crops get reduced due to becoming more susceptible to pests. This notion is now being challenged in Bhutan and by some farmers in Asia, including India, who are developing new, organic techniques to grow more without losing soil quality. Sustainable Root Intensification is one of the organic methods that can potentially double the crop yields. Other agrarian methods are not new. Using traditional crops and their organic seeds, which have pest resistance, can increase food production without the help of synthetic chemicals.

GNH Vs. GDP

GDP, or Gross Domestic Product is the market value of final goods and services produced by a country within a given period of time. GDP is the modern indicator of a country’s standard of living and the wellbeing of its citizens.

The Kingdom of Bhutan (official name of the country) has, since 1971, rejected GDP as the way to measure progress. Instead they measure their country’s prosperity through formal principles of Gross National Happiness, GNH. GNH is determined by the country’s spiritual, physical, social, and environmental health.

The belief that wellbeing should take preference over material growth is clearly at odds with the rest of the world. I can imagine that some may consider GNH naive and credulous and that others may even make fun of it. But in the face of global economic and environmental crises, Bhutan’s GNH is becoming an attractive idea.

The principles of GNH are taught in Bhutan’s schools. In addition to regular secular subjects, students learn the basic techniques of agriculture and environmental protection; they engage in daily meditation sessions and have replaced the alarm-like sounding school bell with soothing traditional music, all due to following this paradigm of GNH.

Choki Dukpa, the head teacher at a primary school in Thimphu, the country’s capital, said in an interview that education doesn’t just mean getting good grades. It means preparing students to be good people.

Challenges

Things are not completely rosy in the country of Bhutan. There are challenges.

Bhutan’s government is aware that their green initiatives and the Gross National Happiness model may not survive the collision with the increasing environmental and social challenges of the rest of the world.

Bhutan shares the planet with the rest of the world’s population. If other countries are not carbon neutral, the abnormal climate changes will affect Bhutan as well. “Bhutan is a mountainous country, highly vulnerable to extreme weather conditions. We have a population that is highly dependent on the agricultural sector. We are banking on hydropower as the engine that will finance our development.” – said Thinley Namgyel, the head of Bhutan’s climate change division. The erratic climate behavior is making it more and more difficult for farmers to successfully produce food. Sometimes there is no snow in the winter, the rains come at wrong times, thus plants get ruined. As the temperatures get higher, there are more insects in the fruit and grain. In extreme circumstances, government sometimes has to distribute fertilizers and pesticides to help people save their crops.

The other challenge for Bhutan is the seduction of their youth by the decadent modern world. The youth is losing interest in farming. Many are moving to the capital or other countries, leaving agriculture to their aging parents. More and more, especially youth, want to use modern facilities, such as cars. Since the country does not have its own oil, it has to import it from other countries, thus unbalancing the import-export scale and pressurizing the country into commercialization.

Upon being interviewed, a group of teenagers in Paro, a town in Bhutan, said they want to be forest rangers, environmental scientists, and such, but at the same time they want to travel the world and enjoy its modern not-necessities such as cars, pop music, and watch movies such as Rambo.

Another teenager, 15-year-old Kunzang Jamso, thinks that “We need to keep the outside from coming here too much because we might lose our culture.”

Much of Bhutan’s healthy goals and attitudes, which seem to be conspicuous by their absence in the world of business and politics, are stemming from their history of spiritual thought and culture.

Krishna teaches in the Bhagavad-gita (2.66) that one without spiritual connection can not have transcendental intelligence nor a steady mind, without which there is no possibility of peace. “And how can there be any happiness without peace?” Krishna asks. However, for some bizarre reason most of the world seem to equate business victories and economic gain with happiness. But the two have little in common. Bhutan appears to have understood it.

Bhutan is setting a good example for the rest of the world, but all of that could be undone if other countries don’t make a move in the right direction.

Signing off. OM TAT SAT. Hare Krishna.