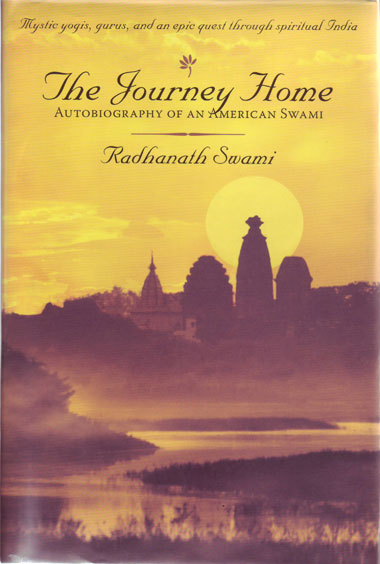

BOOK REVIEW of: Autobiography of an American Swami

By Radhanath Swami (San Rafael, CA: Mandala Publishing, 2008)

Every now and then a book is released which becomes a spiritual classic–a book that brings people in touch with a distant world, opens minds to new possibilities and becomes standard reading for spiritual seekers. Autobiography of a Yogi and Be Here Now come to mind. With the release of The Journey Home – Autobiography of an American Swami, I believe Radhanath Swami has given the world a new spiritual classic, one destined to both fascinate minds and touch the hearts of thousands. In recent memory, most presentations of bhakti that have arisen in the mainstream have been done by those not thoroughly seasoned in the practice itself. For instance, Deepa Mehta’s film Water and Elizabeth Gilbert’s book Eat, Pray, Love both have something interesting to offer, but neither can provide the appreciation of an insider. Therefore, I’m particularly delighted to see a presentation of bhakti-yoga enter the mainstream from a such a worthy practitioner.

The Journey Home is a spiritual memoir—the real-life, autobiographical account of an exceptional countercultural youth who leaves America in search of himself. Trying desperately to access the continent within, he sets out first for Europe, visiting cathedrals, holy places, and hippie hotspots. With little more than a seeker’s heart and a blues harmonica, he leaves few avenues unexamined, as his overland journey takes him through the Middle East and beyond. Western religious ideals and the models who exemplify them are his first natural guideposts and ports of call. He is open, nonsectarian and, most of all, earnest.

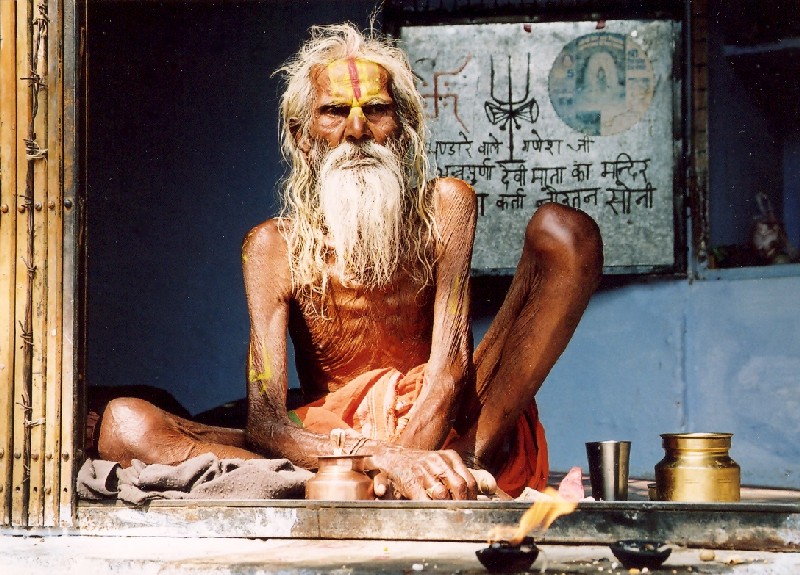

Ultimately, he arrives in India by the end of 1970, where he finds himself living the life of a wandering sadhu, a mendicant, with little money and fewer resources. His travels lead him in many directions, both geographically and philosophically, and the reader watches him age with the wisdom of centuries. In a few months, his young world is augmented by experience and realization. We accompany him into a magical land of yoga, meditation, and soul-stirring revelations. At various points in his journey, he meets deformed lepers and frightening Naga Babas, contemplative Buddhists and mystic yogis—even old friends from the West and angelic devotees.

Through the author’s personal encounters, the reader is introduced to many of the prominent yogis, monks, and gurus of the era—Swami Shivananda, Swami Rama, Swami Satchidananda, Swami Chidananda, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Ananda Mayi Ma, Neem Karoli Baba, Muktananda, even the Dalai Lama and Mother Teresa—either directly or through their legends and teachings. We meet many nameless luminaries as well, and those whose names, if not for Radhanath Swami, we would have never heard. Our blossoming seeker meditates under the original Bodhi Tree—the Buddha himself meditated and achieved enlightenment here!—and studies with masters and saints.

Each experience inches him closer to his goal. We witness, with him, the burning of dead bodies in Benares and fascinating pilgrimages to ancient cities (and inner worlds) where life takes on new meaning, high in the Himalayas, Tibet, and in holylands innumerable. He lives in caves, deep in forests, under trees, and moves throughout the subcontinent with a thirst for “the truth” that is rarely seen—anywhere.

The book is replete with touching, heartwarming (and sometimes heart-rending) episodes—like when he rejects the advances of a beautiful woman for the sake of his quest, or when he feelingly and with tears bids his harp goodbye, throwing it, once and for all, in the River Ganges, or when he meets his eternal guru. All such scenes are recreated for the reader with deep emotion and storytelling expertise. Both descriptive writing and perceptive analysis are plentiful in this book, making it a precious gem that will enrich the reader with its shining brilliance.

The meeting with his eternal guru is, in many ways, the pivotal episode in the book. It was on this momentous occasion that all he had learned would suddenly gel for him. The Indian print of Lord Krishna our young seeker had carried with him for numerous months, uncontrollably attracted to it, now had personality, definition—it was the Supreme Lord as evoked in the Hare Krishna Maha Mantra. This sacred chant, too, was something he had carried around for many moons, having mystically received it through the grace of the Ganges River. But now, by his guru’s grace, he was able to connect the form with the mantra, the Godhead with His spiritual sound vibration. It all came together, like the three rivers—the Ganges, the Yamuna, and the Sarasvati—in Prayaga. Still, his quest continued, even after meeting his master, just so he could be sure that he had left no stones unturned.

But it was in his master’s eyes that he found his way home. This is where he discovered the true depth of the Ganges and the ultimate meaning of the Himalayan masters; the value of lineage holders and the wisdom of the Vedas; the secrets of mysticism and the heart of devotion. His master’s very being spoke of purpose, mission, and unending love. Home, too, was in Vrindavan, Lord Krishna’s holy playground, which embodied his master’s essence.

Throughout this work, we find the author’s culminating realizations, as well as correspondence written to family from distant lands, set apart from the rest of the text, both with italics and with inset block quotes. These are often pithy and rich, thought-provoking and even profound. In fact, the block quotes, along with the book’s picture sections, showing the author as a youth, with family and friends—so one can visualize the main players in his life—and with spiritual “celebrities,” such as the Dalai Lama and others, add immeasurably to the book’s overall effect.

After trekking for months through hostile lands, often barely escaping with his life, he approaches the threshold of an eternal and magical realm where, realizing that he has at last reached the precipice of his spiritual goals, of Bhakti, or devotional mysticism, he makes the astonishing and almost anticlimactic decision to leave. He returns back to the world from which he came in order to share what he has learned.

It is an extraordinary choice, given what he survived to get there: a journey filled with bizarre and often dangerous characters; mystical, life-altering experiences; treacherous encounters that left permanent marks on him and on those around him. The narrative of that journey unfolds as an engaging tale, a love story, and an education in spiritual reality in all its forms. We are with him through solitude; when he stumbles upon saintly and accomplished teachers; and as he experiences moments of splendor and enlightenment. The fact that he graphically and effectively conveys all this is quite an achievement for a first-time author.

The act of turning back, of potentially denying one’s own salvation so that the world may benefit, holds a revered place in most wisdom cultures. Bodhisattvas, the “enlightened beings” of Buddhism, are motivated by such a wish and forego their own entrance into nirvana, the state of enlightenment, in order to work for the progress of society. In the Jewish faith, the tzaddikim or “righteous” men and women (tzidkanit) are great souls who strive to uplift the oppressed and establish justice. The history of Christianity bears testimony to the price paid by Christian mystics, apostles and martyrs who served as conduits for the spirit of God in the world. And in India the title sadhu is awarded to learned spiritualists who embody the holy life and serve as teachers and guides.

Not all sadhus risk their spiritual attainment to help others.

In traditional India, there are basically two types of sadhus. One type is called bhajananandi. These are sadhus who shun society and live in forests or caves, where they devote all their days to intense penance, rigid study, and sing bhajans, sacred hymns. They remain aloof from money matters, their diet is austere, and for most seekers of enlightenment their path is impossible to follow. The other sadhus are known as goshtananandi. These sadhus travel to populated cities to give everyone a chance to hear about God and the principles of a holy life. Their path requires them to confront one of the greatest challenges of the divine call, namely how to live a holy life in utterly unholy surroundings. They show it is possible to remain egoless in an ego-driven environment. Simply put, their teaching is as follows: how to be both in the world and yet not of it.

According to a brief Author’s Note at the back of his book, Radhanath Swami emerged from his years of travel wanting to explain for others the beauty and mystery of what he had discovered, and therein lay a dilemma. Judging by this very intimate account, he is a shy soul who finds it uncomfortable when a spotlight is focused on him. Writing an autobiography was just not his style, but he undertook the exercise in response to appeals made by a number of his admirers. One friend in particular, Bhakti Tirtha Swami (1950–2005), was an African-American guru who had risen from an impoverished childhood to become a Princeton graduate, civil rights activist, High Chief in the Warri kingdom of Nigeria, and a spiritual leader with students on five continents. He was also one of the few people in the world who knew the full scope of Radhanath’s odyssey. In 2005 as Bhakti Tirtha Swami lay dying from cancer, he made a request. He asked Radhanath to set aside his reservations and write the story of his journey to God. At first Radhanath refused, saying that writing about his own life would be “sheer arrogance.”

“Don’t be miserly,” Bhakti Tirtha told him. “Share what has been given to you.” He passed away two days later.

In some ways, Radhanath Swami’s hesitation over coming back into the world after his discovery of Bhakti was justified. After all, having gone through the numerous experiences related in this book, his was now the peaceful and fulfilling life of an accomplished recluse; why take backsteps into the drudgery of material life? Associating with those focused on sense gratification, he knew, would engender the worst of risks. But his ultimate choice, in terms of path and teacher, tells the story. At this point, we can let the name be known: By selecting Srila A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896–1977), a pure devotee—an activist, who lived only to help others—as his guru (after declining offers of initiation from several yogis and other adepts in the Himalayas and elsewhere), Radhanath Swami cast his fate to the wind, cut his matted locks, and bought a ticket back to America. More than a symbolic gesture of moving away from the mindset of physically renouncing the world, these were first steps toward an “engaged” form of devotion. This contemporary strain of the Bhakti tradition maintains that people who are aware of their spiritual identity must help to reduce suffering in the world around them. They must share what they’ve been given.

Every recent generation has had its best selling mystic guidebook, often focusing on the life of an exemplary seeker. The 1940s gave us works on the lives of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda as well as Paramahansa Yogananda’s now classic Autobiography of a Yogi. Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain, detailing the Trappist monk’s quest and accomplishment, came soon after that. The following decades produced a slew of mystic accounts, prominent among them are Carlos Castaneda’s series on Yaqui shaman Don Juan Matus and the cult classic Miracle of Love: Stories About Neem Karoli Baba. The Ochre Robe, an autobiography written by Agehananda Bharati, dominated the genre in the ‘80s, but there were others.

These first autobiographical books, as listed above, focused on Shaktas or the neo-Hinduism associated with Advaita Vedanta, or on yogis, as in the case of Yogananda. For a Christian hagiography, Merton was decidedly more modern in his approach.

Biographical tales of Yaqui shaman mysticism and of Neem Karoli Baba, both, were tinged by the psychedelic mode of the ‘60s and by generic Hinduism. Agehananda was a Dasanami sannyasi, following the philosophical conclusions of Shankara.

The next generation belongs to The Journey Home. Like its predecessors, it offers readers an intimate look into a true seeker’s life, and into the tradition he ultimately chose to follow. But what is unique here is that the tradition of choice is Vaishnavism. The books mentioned above, and so many others like them, invariably sidestep the Vaishnava tradition. There may, of course, be many reasons for this: Those focusing on Western spirituality need not look at the Vaishnava sages and their theological background at all. It simply doesn’t figure into their survey. But the Eastern texts are another story. With Vaishnavism accounting for the vast majority of “Hindu” practitioners in the world today—a statistic that was initially brought to light by Agehananda Bharati himself—its omission in the pages of the world’s spiritual biographies is inexcusable.

That being said, the time has finally come for Vaishnavism to be given its due, and there is hardly a more worthy representative than Radhanath Swami. Indeed, he has learned from and appreciated every single religious leader and tradition that has crossed his path. He views reality in an unabashedly pluralistic way, never discounting the value and merits of any genuine form of esoteric spirituality. He is nonjudgmental in the best, most enlightened way—as a Saragrahi Vaishnava, one who looks to the essence, seeing all religion as just so many roads to the same goal, which is, of course, God. This makes him a superlative Vaishnava, indeed. Thus, The Journey Home stands tall in the long line of spiritual classics mentioned above—and it richly deserves to be there. It, too, has found a home.

Steven Rosen (Satyaraja Dasa) is an initiated disciple of His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. He is also founding editor of the Journal of Vaishnava Studies and associate editor for Back to Godhead. He has published twenty-one books in numerous languages, including the recent Essential Hinduism (Rowman & Littlefield, 2008) and the Yoga of Kirtan: Conversations on the Sacred Art of Chanting (FOLK Books, 2008).

The Journey Home can be ordered from Mandala Publishing.