The silent tears at the other end said it all. “Is everything alright?” I asked Priya. I have known Dr. Priya Venkat, a pediatrician, for nine years. I was a witness to her strength and determination as she fought through many challenges in her college years. I felt a sense of satisfaction to have personally contributed to her welfare and finally see her settled in a happy married life. That is why her call was tough. Priya, who was six-months pregnant, barely managed to utter the words: “Miscarriage.”

Two conspicuous emotions emerged simultaneously — helplessness and shock. Helplessness because I could not even find the words to console her or myself, and shock because two minutes before I received that phone call, I was talking to my roommate Ari about the fragility of our life and the constant, undercover companionship of our death. Little did I realize that the conversation was just the beginning of a series of deathly events in the span of one week. The news of the miscarriage was followed by a suicide of the 17-year-old son of a good friend, the demise of my 23-year-old student who was suffering from cancer, and finally a fatal heart attack that consumed my 60-year-old cousin.

Thousands of people die every day, and the world still moves on. We read and hear about deaths and tragedies almost everyday in the news. It may grab our attention for a moment, but the sports section seems more interesting. Is death really that trivial? Or have we unconsciously or consciously tranquilized ourselves from its impact?

The topic of death has the wondrous potential of concentrating the mind. It opens up a deeper sense of inquiry into our true nature and makes us question the very purpose of our existence. The Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard once said that the real education of mankind means facing up to death. In most spiritual traditions, especially those from the East, the problem of death seems to open up the doorway to deeper spiritual inquiry.

The Buddha renounced his wealth and riches to seek enlightenment when he saw the unpleasant sights of disease and death and realized that he had to go through the same. Similarly, in the Bhagavad-gita, which is India’s classic text on yoga and spiritual wisdom, prince Arjuna faces a similar existential crisis as he is called upon to fight a gruesome war against his own kinsmen, led by his wily and unrighteous cousin Duryodhana. Although Arjuna was a veteran of many wars, he confronted death like never before because on the opposing side were members of his own family that he deeply loved and respected, but he was forced to fight them because of political intrigue.

The first chapter of the Bhagavad-gita is called “The Yoga of Arjuna’s Crisis” — an appropriate title because the word “yoga” means “to link” or “to connect”. In this chapter, Arjuna’s crisis makes him connect through deep inquiry to his own identity. What follows is a beautifully composed and spiritually profound dialogue between Arjuna and his charioteer and dear friend Krishna. Although I grew up with three different editions of the Bhagavad-gita at home, this text made a much deeper impact on me after my own encounter with death.

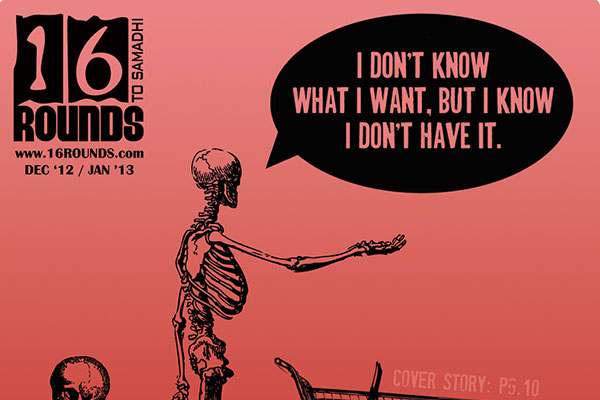

My spiritual journey began when I first confronted the problem of death at the age of 17. After securing admission to the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology, I faced deep insecurity about the fact that all achievements in my life will be invariably stripped from me at the time of death.

The issue was like a thorn in my side until one day, during dinner, I expressed it to my mother. Very affectionately, she mentioned that I was letting such thoughts rob away my real joys of life. It is important to live in the moment and experience life to the fullest. Her affection touched my heart, but her response left me dissatisfied. I felt that her response was urging me to be in denial of the terror of death. It was like trying to enjoy a delicious, elaborate feast on the eve of a really tough exam for which I have not prepared one bit.

Although I pursued the thought for some time, the intensity waned — helped by my own “confidence” of being able to “manage” the world. I invested myself in “hero projects” that I hoped would leave a mark in this world. It was not until my second date with death that I realized that the human brain just does not have the capacity to comprehend the magnitude of the terror.

The rendezvous occurred when I was a first year MBA student at Cornell University in September 2005. I had just finished a major exam in accounting and was one of few students in the class to secure full marks. My performance gave me complete confidence and security that I would ace my MBA program and secure a top job as an investment banker. That same afternoon I proceeded to Cornell University’s medical center for a regular blood test. After the doctor obtained the required samples, I was sitting in the reception area scouring the Wall Street Journal. Suddenly, I saw darkness in front of me.

When I came to external consciousness, I heard screams all around. I was on a stretcher surrounded by a whole bunch of medical personnel frantically rushing me to the emergency room. I felt excruciating pain in my hands and feet. They were twisted in an awkward fashion and to my greatest shock I could not move them. Then I felt numbness creeping up my body from my feet. I could barely speak and my eyes were getting heavier. Much to my horror, I realized that this could well be the end. Every moment seemed dilated. My entire life began to play out in front of me like a movie. All the people that I loved and all the things that I felt deeply attached to filled up my thoughts. The pain of sudden separation from all of them was intense and tears welled up in my eyes. A distinct feeling enveloped me — a state a despair resulting from an inevitable contradiction — the strong desire for immortality in a situation that had mortality written all over it.

I was given heavy dosage of painkillers and other medicines and woke up 14 hours later feeling like I had run a marathon on my hands. I was relieved to be alive. Nothing else mattered at that moment. The doctors described the episode to be an extreme case of a vasovagal reaction or neurocardiogenic syncope — an abnormal reflex to wounds or punctures that results in a blood pressure drop leading to decreased blood flow to the brain. Amazing what a harmless blood test can cause!

This experience opened my eyes to the fact that death could come at any time — even when it is least expected. It only takes a moment for life to change by 180 degrees, and when it does, the first reaction is shock. I say shock because the built-in narcissist in the human psyche believes that he will never die; he only feels sorry for the man next to him. Freud’s explanation for this was that in man’s inner organic recesses he feels immortal.

I once read a story in the Mahabharata, a text on India’s ancient history that resonates well with this. The great king Yudhisthira, who was very famous for his wisdom and unwavering sense of integrity, was once put to a test. He had to answer 100 questions that tested his intellect and wisdom, and his success was a matter of life and death for his dear brothers. Yudhisthira impressed his interrogator with the first 99 questions. The last and the most open-ended question of the test was, “What is the most wondrous thing in this world?” To this, the king deeply pondered and responded, “Every person sees many others around him die everyday, but refuses to believe that he will ever have to go through it. On the contrary, they make plans for a permanent settlement in this world. To me, this is the greatest wonder and the biggest irony!” Of course Yudhisthira won the contest.

Confronting the fragile nature of my existence was a very humbling experience. I realized that at the time of death, the physical body that I so carefully nurture, the adoration and distinction that I strive for and treasure as fortifications of my greatness can all get uprooted and scattered like trees in a tornado. I was forced to re-examine the reliability of social, political and financial power-linkages that gave me the sense of being grounded. Facing the truth of this situation opened up spiritual inquiry yet again. For the first time, the concepts from the Bhagavad-gita made deep and logical sense.

This experience also helped me realize that treating death in a trivial fashion may close doors to deep realizations about our very existence. Life escapes us when we huddle within the defended fortress of our invulnerability. It’s not that we should be paralyzed and depressed at the thought of death and renounce enjoying the precious and deep moments that life has bestowed upon us, but not taking death seriously enough may be as good as not taking life seriously enough. It may very well rob us of the opportunity to develop the humility and gratitude to appreciate the abundant gifts of life.

One bit of profound advice that Socrates gave to his disciples was to practice dying everyday. Although this may sound impractical, the undertone to this insight is very useful — to cultivate awareness of and face our deep-rooted insecurities, the epitome of which is death itself. Such awareness, when dealt with in a healthy and honest fashion, leads to a deliberate dismantling of our defense mechanisms of denial and repression. It makes us take life seriously enough to deliberate on our actions and makes routine activity impossible. It increases the discovery of new possibilities of choice and action and new forms of courage and endurance. It gives rise to a new and more meaningful way of life.